With mapping technology and internet connectivity at our fingertips, it's never been more possible to collect reams of information about how individuals travel and engage with active transportation. 58% of American adults own smartphones, according to Pew Research, and this number is increasing.

A few Alliance member organizations have already taken advantage of this trend.

The Washington Area Bicyclist Association created their own app to empower bicyclists in the greater DC area to collect vital information in the event of a crash; the data are submitted to WABA and becomes a basis for enforcement-related advocacy. Farther north, the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia has worked with civic hackers to create bicycle activity maps, a bicycle counting app, and, most recently, crowdsourced maps of where Philly bikers ride. New Hampshire has taken a different approach: Tim Blagden from the Bike-Walk Alliance of New Hampshire paved the way for the Department of Transportation to purchase Strava data.

On yesterday's Alliance Mutual Aid webinar, advocates from these three different organizations discussed their three different approaches to utilizing apps and app data in their work to improve biking.

Missed the session? No worries. Check out the recording below and read on for some of the big takeaways. Members can access notes from the call in the Alliance Resource Library.

1. Robust crash reporting makes for better enforcement advocacy

For years, the Washington Area Bicyclist Association has been helping area bicyclists who have had the misfortune of being involved in a crash.

Even before WABA developed an app, they handed out a pocket guide to DC's bike laws, complete with a page on what to do in case of a crash. They also added a bicycle crash reporting form to their website, which feeds directly into their Salsa database and helps the organization track crash trends and common police responses. Advocates held seminars on what to do in case of a crash and coached individual riders who faced post-crash issues.

According to webinar panelist and WABA advocacy coordinator Greg Billing, the organization always wanted to create a mobile app to collect more data. When the New York Bike Lawyers came out with a simple crash app, WABA reached out to ask about how it worked and who built it. Greg's team struck a deal with the same developers, and the WABA app was born.

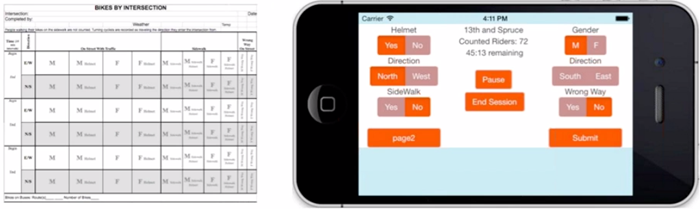

A screenshot of the WABA crash app on iPhone. Image: Greg Billing

WABA's app helps users record all the right information about a crash (and submit that information to WABA), log their exact location, and take notes and photos. It also includes safety tips and a DC bike law guide.

About 1,000 people have downloaded the WABA app for both Android and iPhone.

Thanks to user-submitted crash data, WABA has a better understanding of the biggest issues with police enforcement. For example, advocates learned that police commonly misuse the "riding abreast" law in DC. These data have helped WABA collaborate with the police department to improve enforcement and highlight compelling stories for media coverage and official testimony.

2. Philly's civic hackers help advocates improve biking for everyone

The Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia has found fertile ground in partnerships with civic hackers. Through groups like Code for Philly, the Bicycle Coalition has tackled several projects that marry the power of civic-minded software engineers with the need for better data for bike advocacy.

John Boyle, the Coalition's research director and a panelist on yesterday's webinar, said that the coalition's first interaction with mapping data arose through a competitive GIS mapping program run by local mapping firm Azavea. Under the Bicycle Coalition's guidance, Azavea built a suite of maps to look at bike crashes, thefts, and travel throughout Philadelphia.

The second interaction arose after the Coalition received an invitation to participate in a civic hackathon. In response to the need for a less time-intensive way to manually count bicycles, Philadelphia coders created a bicycle counting app. The Bicycle Coalition will have a chance to test out this app when they next perform annual bike counts; they hope for big reductions in time spent entering data.

Left: the paper sheets that Bicycle Coalition staff and volunteers use to count bicyclists. Right: a prototype of a new bike count app. Image: John Boyle

The Bicycle Coalition has also supported CyclePhilly, a new smartphone app that records bicycle trips.

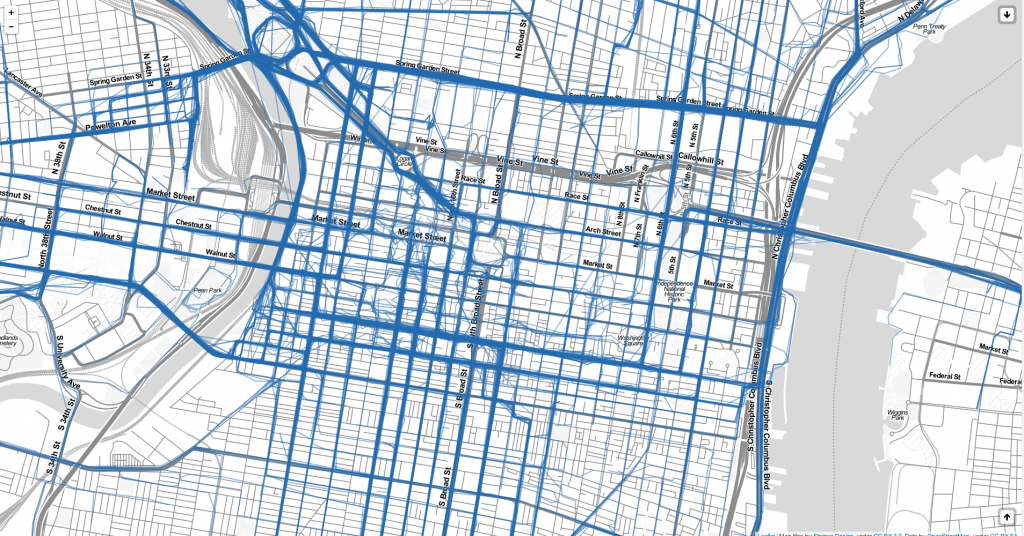

CyclePhilly's crowdsourced map shows popular bike routes in Center City. Image: BCGP / CyclePhilly

Corey Acri, one of the developers who worked on the app, joined the webinar to discuss the process behind developing CyclePhilly. (Alliance members can read more in the Resource Library; Corey also documented his work in this great blog post.) Data from the app go directly to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission – Philadelphia's metropolitan planning organization – and are available to the public in map form. CyclePhilly has tracked over 10,000 trips by about 270 individual cyclists.

John hopes that the Bicycle Coalition will be able to utilize CylePhilly app data to show common bike routes in the Philadelphia suburbs, where it's harder to count ridership. He hopes that in the future, the app could be integrated with other ride-tracking apps or the National Bike Challenge to create an even more robust dataset.

3. Using existing datasets to make cyclists visible

When Tim Blagden started as executive director of the Bike-Walk Alliance of New Hampshire, he wasn't sure exactly how to tackle improving bikeability in the Granite State. But as a member of the state Department of Transportation's Bicycle Pedestrian Advisory Committee, he quickly learned that state policymakers have very little grasp on where people already ride their bikes.

DOT staff, Tim explained on the webinar, didn't know where people were riding unless there was a crash.

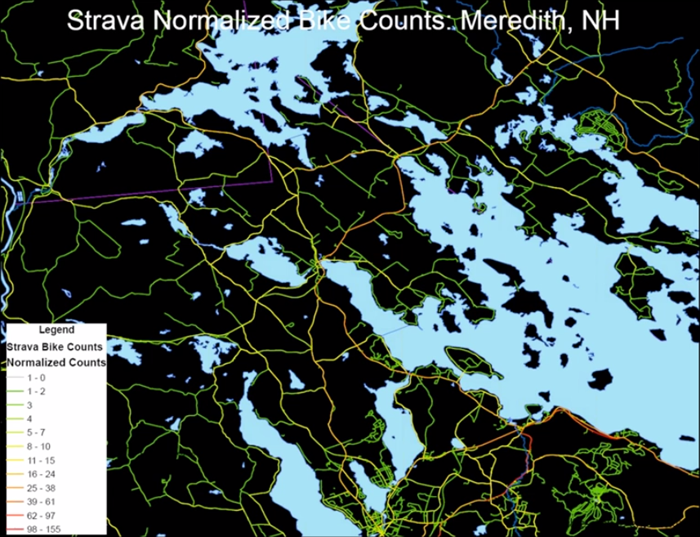

To help the agency understand where cyclists travel and when they do it, Tim contacted a variety of mapping companies. Strava, the popular running and cycling tracking app, was ready to bundle the data for NHDOT and deliver it directly into the agency's native GIS system. The cost would be less than $10,000 for a robust sample showing every rider in 2013, with trips broken down by day and hour.

Strava data shows bike rides in Meredith, New Hampshire. Image: Tim Blagden

The Department of Transportation agreed to make the purchase. Advocates and agency staff are now working on how to best use the data.

The Strava dataset is a sample, and Tim emphasized that these data will need to be supplemented with other types of counts. The Oregon DOT made a similar purchase and found that Strava riders represented 1 - 3% of total bike ridership. Tim hopes that combining Strava data with regular bike counts and new route analysis methods, like low-stress network connectivity analysis, could produce a robust, data-driven and irrefutable understanding of where routes need to improve.

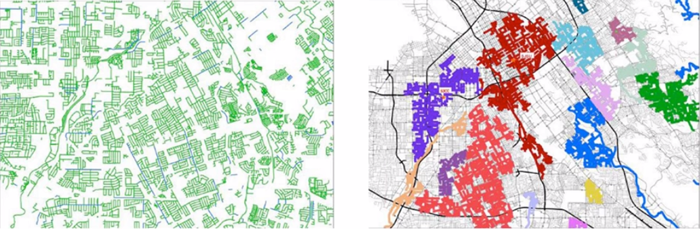

Tim hopes to see Strava data layered with a stress network data, which can identify areas that are isolated by un-bikeable streets. Image: Tim Blagden / Mineta Transportation Institute

No substitute for on-the-ground work

Advocates on the webinar agreed that while apps present promising opportunities for advocacy, they do not replace the need for local knowledge. Many advocates would report that there's no replacement for community outreach and in-person analysis to find out which streets need improvements for walking and for biking.

A key issue, raised in a question by Barb Chamberlain of Washington Bikes, is equity: don't smartphone apps penetrate wealthier demographics, leaving lower-income cyclists out of the dataset? Although smartphone connectivity is becoming more widespread among low-income Americans, at-home broadband connectivity and smartphone ownership both remain lower in low-income American households than households in higher income brackets.

For these reasons, of course, advocates shouldn't give up on-the-ground advocacy outreach tactics in favor of pouring over SQL databases all day. But the right combination of data and local knowledge could present enormous opportunities.

Love this? Please consider sharing.

| Share on Facebook |