Earlier this month, headlines pronounced a new era of transportation choices for a city obsessed with cars. With 300 miles of protected bike lanes, the adoption of Vision Zero and a central commitment to safety, the new mobility plan passed by the Los Angeles City Council has advocates across the country talking. And with good reason.

Earlier this month, headlines pronounced a new era of transportation choices for a city obsessed with cars. With 300 miles of protected bike lanes, the adoption of Vision Zero and a central commitment to safety, the new mobility plan passed by the Los Angeles City Council has advocates across the country talking. And with good reason.

“For the first time ever, the City of Los Angeles is proposing safe and dignified transportation for all residents, whether or not they have access to a car,” Tamika Butler, Executive Director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, said in a statement this month. “The era of widening streets to accommodate more traffic is over. This plan makes smarter use of the streets we have by prioritizing more efficient forms of transportation. During years of community outreach, residents asked for real options. By improving transit and biking on just a fraction of city streets, more people will be able to get around Los Angeles without getting stuck in traffic.”

Those headlines were made possible, in part, by countless hours from LACBC working behind the scenes and guiding the fine print of a plan that provides a model for other major cities nationwide. So what went into the effort — and what impact has it had on, not just the city, but LACBC? I hopped on the phone with Butler and Eric Bruins, LACBC’s Planning & Policy Director, to find out more.

Cultivating consensus

While many have been following the #LA2B as the debate reached a peak over the past several weeks, LACBC has been involved in conversation since its start four years ago. At that point, the organization was energized by another major victory — the passage of the progressive 2010 Bike Plan — when it became a member of the city’s Mobility Plan Task Force.

While many have been following the #LA2B as the debate reached a peak over the past several weeks, LACBC has been involved in conversation since its start four years ago. At that point, the organization was energized by another major victory — the passage of the progressive 2010 Bike Plan — when it became a member of the city’s Mobility Plan Task Force.

“We went into the Mobility Plan process having just completed a successful bike plan, so there were moments we were having to watch to make sure we weren’t accidentally undoing the progress we’d just won,” Bruins says. “But it was also a huge opportunity because back in 2010 and 2011 protected bike lanes weren’t legal in California, so we didn’t plan for them in the bike plan. The biggest gains and our focus in the Mobility Plan were how to plan for 8-80 [bikeways].”

For LACBC, the process itself was a key opportunity to not just guide the creation of a strong mobility plan, but to build new relationships — and cultivate leaders from other sectors. One notable example was the business community, with LACBC working closely behind the scenes with influential entities like the Chamber of Commerce and Los Angeles County Business Federation.

“We were very much on the same page with them, and were able to help shape their talking points to reinforce what we cared about in terms of keeping our networks intact and creating a balanced plan,” Bruins says. “That was really exciting.”

With a new focus from the city on integrating health and equity into the conversation, the plan became an avenue to exciting intersections between typically siloed — or opposing — issues, as well.

“We were doing Twitter conversations and online actions and some of the main environmental justice organizations were tweeting alongside the Chamber of Commerce,” Bruins says. “That’s so rare. There was really broad consensus.”

Leading from behind (the scenes)

Leading from behind (the scenes)

The LACBC was strategic about working with those groups as the public-facing champions for the mobility plan — rather than taking the spotlight themselves and making cycling the central issue.

“We intentionally did not lead this plan publicly,” Bruins (pictured right) says. “We wanted it to be seen as balanced. We didn’t want it to be, ‘The bike coalition wants this plan.’ We did a lot of logistical legwork, but we didn’t want to directly own the advocacy publicly, too.”

They didn’t want to dominate their interests above all others, either. Instead, the LACBC also recognized the power of letting go — and allowing for the possibility that, in some cases, better mobility could mean scaling back provisions specifically targeted to cyclists.

“In the past, when we were putting bike lanes on major streets, we weren’t really worrying about what that meant for buses,” Bruins explains. “In this plan, we were more strategic in thinking about the impact on the transit network, [because] transit is how a lot of folks--especially low-income folks of color--move around the city. The mobility plan is really the first comprehensive look at what an improved bus system looks like for the city, and, in some cases, that means compromising bike lanes on a few streets.”

For Butler thinking about bicycling as one part — albeit a very significant part — of the greater transportation network is a key aspect of a very concerted change for the organization.

“I think it’s definitely a conscious shift we’re making in all the work we do,” she says. “We don’t want to turn this into a bikes versus cars scenario. It’s about walking. It’s about rapid bus lanes. We’re recognizing the nuance that furthering that narrative that one mode is better than another isn’t helpful. Yes, we care about bikes — we believe they’re a social justice tool and they’re the means for what we do in our policy work. But it’s tied to a bigger movement for folks to be able to be mobile in their communities, to have equitable access and to own their streets.”

Mobilizing their base

Mobilizing their base

That’s not to say that LACBC didn’t fire up their passionate base of bicyclists in support of the mobility plan. Quite the contrary. In addition to new or enhanced partnerships, this campaign was also a watershed moment for the LACBC in mobilizing its own members and constituents. In the past, Bruins says, a call to action might garner a few dozen calls or emails to city officials. But, combining on-the-ground organizing and social media strategies, like Mobility Monday, LACBC unleashed a tidal wave of citizen involvement.

“Telling folks to email their council member and then Tweet the fact that they did it, getting that social sharing, the response was multiple times what we’ve ever had — with hundreds of emails going to council members,” Bruins says. “And because a lot of the controversial issues related to projects where we had on-the-ground campaigns over the past several years, where we had been doing a lot of base-building in those communities, we were able to activate people to really turn out to keep those projects in the plan.”

That public push was vital. While the 2010 Bike Plan passed unanimously, the Mobility Plan generated more contentious debate, passing 12-2 earlier this month. But, to Bruins, that increased debate is actually evidence of progress. “Over the past five years, we’ve had a political reality check,” he says.

As the rubber has hit the road on projects in the bike plan, the real-world implications of better bicycling have come to the fore — with elected officials hearing (sometimes loudly) from both supporters and detractors. It’s no longer an abstract concept, but a hot constituent issue.

“Now, the leaders voting for this are serious about the shift — they understand what it means on the streets and they voted for it anyway,” Bruins says.

The biggest wins...

The biggest wins...

The passage of the plan has set the stage for major changes on LA streets. From a policy perspective, the biggest win is the commitment to Vision Zero — and that goal’s integration into the city’s General Plan.

“This puts safety as the first priority for every transportation project,” Bruins says. “In California, every single project the city ever does has to be evaluated with its consistency with the General Plan, so this is an incredibly valuable tool for us. If a project isn’t consistent with the General Plan, that’s something we can point to, with legal protections behind it. That’s a huge deal.”

Another significant win? Changing how progress is measured.

“Before, we were trying to achieve multimodal objectives — but only measuring cars,” Bruins explains. “The State of California has been developing measures aimed at reducing VMT [vehicle miles traveled], while cities like LA have been focused on level-of-service. This plan is about trying to get those policies to line up. We’re developing metrics around what it means to have high-quality transit or bike infrastructure, so we’re able to measure those objectives too, not just moving cars.”

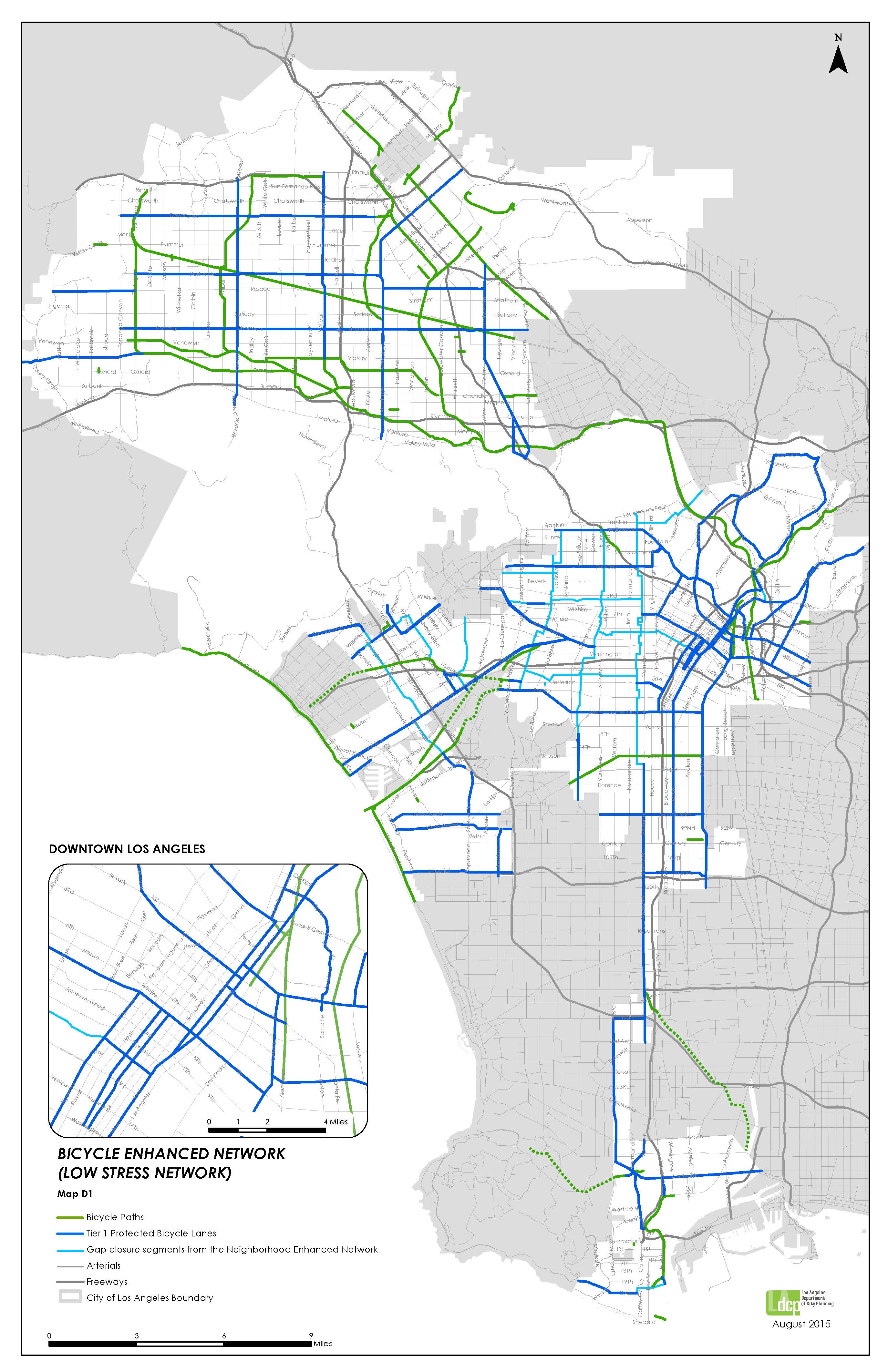

On the infrastructure side, the Mobility Plan also includes a huge boost for protected bike lanes — 300 miles of them (map right).

“We kept the Bike Plan as the base map and layered on all these value-added protected bike lanes and enhanced bicycle boulevards onto the basic network,” he adds. “So we were able to keep everything we won in 2011 and then up the priority and quality of a subset of the 2011 plan.”

But the campaign continues

While the plan’s passage was a massive victory, the wins for bicycling aren’t entirely secure — yet.

“When they passed the plan, the Council tabled the more controversial amendments, which would take out chunks of the bike plan,” Bruins says. “It will be reconsidered in the next month, so, while we clearly won this round, we’re not done. There are specific efforts by several council members to gut parts of the plan, so we’re very much active and organizing around those amendments.”

Stay tuned to the Alliance Roundup and follow @lacbc, @tamikabutler and @ejfbruins on Twitter to stay up-to-date on those continued efforts!